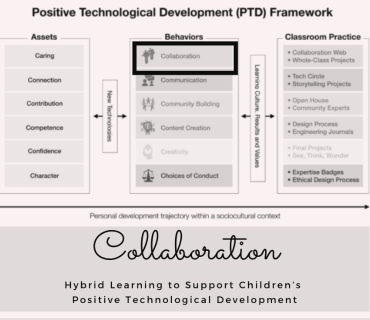

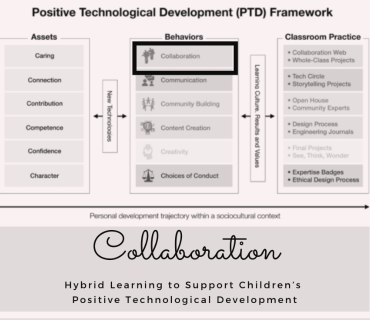

This blog post is an installment in a six-part series of posts about supporting children’s Positive Technological Development through hybrid/distanced learning.

Full Story

Activities for Home and School

Activities for Fostering Communication Skills From Home.

Collaboration is difficult to practice in an isolated/distanced setting. In these at-home collaborative activities, invite students to collaborate as a class to create pieces of art or expression through technology that represent all children collectively. This gives students experiential and concrete ways to see themselves as a collaborator within a larger class community.

Collaboration Game: Virtual High Five. This at-home activity involves working with children on gallery mode in Zoom to give a virtual high five to the person next to them. Ask them to turn on the grid view in Zoom. Model how you give a virtual high five to one student (see image 5). Then assign partners to practice. Practice this a few times until everyone has had a turn, then see if you can pass the high five across the room and challenge students to pass the high five one at a time as it travels around the room.

-

This activity works best if you have set a virtual seating chart ahead of time (see instructions to create virtual seating charts on the Zoom blog), or you can invite children to high-five with both hands (left and right), so they connect with a partner no matter who is next to them.

-

For younger children who might find this spatially challenging, you can also have them hold their hand directly in front of the camera at the same time, so the effect is a group high five of hands around the screen.

Image 5 shows the authors giving a virtual high five in Zoom!

Collaborative Music Projects. During a Zoom meeting, invite children to compose a song together as a class. Take time to explore the Google Chrome Music Lab Song Maker, a software that lets you make music using a simple interface. A few labs we suggest are the Shared Piano, Song Maker, and Arpreggios! Share your screen and demonstrate how to access Google Chrome Music Lab, then test your song and then to show how your clicks change the sound of your song. Once students are curious and ready to try, share a link to your unique song to individual children in the chat and ask them to add to your song. You can keep screen-sharing to show their work-in-progress, or reveal after they have added in their melody. Continue to add to the class composition over time, until everyone has had a chance to contribute. You can organize a “musical performance” for families at home by emailing a link to the finished song, and sharing a short written or video explanation of this collaborative musical expression of your class community!

-

You can prepare children for this activity by participating in call-and-response songs during morning meetings that involve children’s names. This reminds them to focus during large-group video calls, because they could be called at any time!

-

You can find thematic songs about technology by exploring the book, Technology is All Around You: A song for budding scientists.

Safety Tip: If you are planning to start this activity in-person, avoid having children sing, as this can spread COVID via droplets in the air.

Collaborative Art Collage. Invite children to contribute to a class collage by bringing a piece of art or a meaningful object to a Zoom morning meeting. Model how to hold an object up so it is clear to see in the camera (for ideas check out this video of a young child participating in Zoom Show-and-Tell). Invite children to take turns in Speaker mode sharing about their object, and end in Gallery mode by having everyone hold up their object at the same time while you take a screen-shot. This image is a collage of meaningful objects representing your class! You can try the activity asynchronously by having children send a picture of their object to you, and pasting it into a document or slide presentation afterward or hosting the activity on Flipgrid. Don’t forget to share the finished collage and a few sentences of explanation with families afterward! You can continue to use and add to this collage throughout the year.

Activities for Fostering Communication Skills At School.

One important way to lay a collaborative foundation for your classroom is to have children practice creating artifacts that they know ahead of time someone else will alter or contribute to. In the following activities, children can practice working on contributing in a creative way to a larger group project that will be new and unique from what they would have made alone.

ScratchJr “Pass It On” Project. Invite children to create a project using any characters, blocks, and background images they like. Make sure to tell them before the activity starts that these are play-projects that they won’t keep working on later. Give students a limited amount of time to work (between 2-3 minutes is a good length), and when time is up, have them swap projects with a classmate. You might lay devices on a table, and have children walk around the table to avoid making them carry devices. Give them another few minutes to work on a project someone else started. Have children continue to swap as many more times as you like.

At the end of the activity, display the finished projects to the class on a projector. This is the fun part! Model for children how to take joy in the new creation that many programmers contributed to. Ask children if they can identify which parts of each project they recognize. Often children learn new blocks or features after playing with a project started by someone else, which you can also discuss as a class.

Tips for children who aren’t ready to lose their work: It’s very important to remind children that the project they start will be changed or gone at the end of the activity, to avoid confusion and hurt feelings later. You can also invite them to say “thank you and goodbye” to their projects as a way to give some closure. Even with scaffolds, sometimes children become quickly attached to projects they make. Sharing projects via the internet saves a copy of the original work, which can be helpful if a student is not yet ready to accept someone else altering their project permanently.

Safety Tip: To adapt for a socially distant environment, consider using handwipes to sanitize devices between uses, or have children share projects to each other over the internet (instructions for project sharing can be found on ScratchJr.org).

ScratchJr Collaborative Project. Once children are comfortable with playful collaboration, they are ready to try something more advanced like a ScratchJr multi-tablet project. Children must code several projects using shared project assets (characters and backgrounds) and place tablets next to each other to make it seem like a project is taking place across many tablet screens at once. With a multi-tablet collaborative project, the images and movements can span across multiple screens to make their story even more dynamic. You could start by having children create a collaborative collage. For example, children can decorate and code a firework display individually, but all agree to use a black background so that when the tablets are lying next to each other, it creates a night-sky effect with many fireworks.

With multi-tablet projects, the characters on each tablet can be programmed to play at the same time or even staggered to make them appear to move between tablets. The projects can have one overall theme (e.g. a cultural holiday or dance) or tell an elaborate story (e.g. a favorite children’s book or a memorable event). Learn more about multi-tablet project ideas with the ScratchJr Collaborative Project Guide.

Guest Contribution: Research on Reaching Girls in Early Childhood STEM, by Amanda Sullivan.

While many educational STEM programs focus on competition (think of LEGO and VEX robotics competition leagues, for example), research has shown that female students are often more drawn to collaboration and a chance to work toward exhibition style projects as opposed to competitions (Rusk, Berg, & Resnick, 2005). In fact, even women with high levels of computer self-efficacy are drawn to cooperative learning styles (Salminen-Karlsson, 2009). The traditional emphasis in computer science education on competition may be part of the reason why women remain underrepresented in STEM fields like engineering and computer science (Sullivan 2019). The issue of female representation in STEM begins way back in early childhood, when children are first forming ideas about gender roles, identity, and their interests – making early educational interventions so important!

There is also a pervasive stereotype of the solitary “nerd” computer scientist or engineer, hunched over a computer working alone on lines of code. One way to break this stereotype and reach girls (and more people in general) is to hone in on the social and collaborative side of STEM through group projects and brainstorming sessions. Being thoughtful about group pairings is something adults can be mindful of. In one study of young children (average age 7 years), researchers found that girls were careful and less likely to take risks to achieve the task compared to boys or boy/girl pairs working together (Yelland, 1993). All young children need safe spaces to take risks and learn from mistakes in order to thrive in STEM, and beyond.

Family Tip: Collaborating with your child is a powerful way to support agency and equitable role-taking. Beyond this, it gives you a chance to role-model your own positive STEM mindsets. Consider involving your child with basic household tasks that have a STEM component like assembling furniture, fixing something that is broken, or even cooking! Make it an even more positive experience by being mindful of what you say and how you say it.

For tips on inclusive communication with children, check out this infographic Angie created, inspired by the research published in Dr. Amanda Sullivan’s book, Breaking the STEM Stereotype: Reaching girls in early childhood.

How are you fostering collaboration in your classroom this year?

In this post, we share some of our thoughts with you but we REALLY want to hear from you. What has worked in your setting? What have you tried that didn’t work? What lessons did you take away, and what advice would you give a colleague over coffee? Reach out to us on Twitter @mrskalthoff, @ALStrawhacker, and @AASully

References

Bers, M. U. (2020). Coding as a playground: Programming and computational thinking in the early childhood classroom. Routledge.

Microsoft Reporter (2018, April 25). Girls in STEM: The importance of role models. Microsoft News Center Europe. Retrieved from https://news.microsoft.com/europe/features/girls-in-stem-the-importance-of-role-models/

Rusk, N., Berg, R., & Resnick, M. (2005). Rethinking robotics: Engaging girls in creative engineering. Proposal to the National Science Foundation, Cambridge. Retrieved from https://www.media.mit.edu/publications/rethinking-robotics-engaging-girls-in-creative-engineering-2/

SalminenâKarlsson, M. (2009). Women who learn computing like men: Different gender positions on basic computer courses in adult education. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 61(2), 151-168. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820902933254

Schonert-Reichl, K. A., Smith, V., Zaidman-Zait, A., & Hertzman, C. (2012). Promoting children’s prosocial behaviors in school: Impact of the “Roots of Empathy” program on the social and emotional competence of school-aged children. School Mental Health, 4(1), 1-21.

Sullivan, A. A. (2019). Breaking the STEM stereotype: reaching girls in early childhood. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

Yelland, N. (1993). Young children learning with LOGO: An analysis of strategies and interactions. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 9(4):465-486

About the Authors

Angie Kalthoff is the Product Manager for Curriculum and Instruction at Capstone. Over her career, she has been an English Language (EL) teacher, Technology Integrationist, Program Manager, and University Instructor. She has an M. Ed in Teaching and Learning. Connect with Angie on Twitter: @mrskalthoff and visit her website: bit.ly/angiekalthoff.

Angie Kalthoff is the Product Manager for Curriculum and Instruction at Capstone. Over her career, she has been an English Language (EL) teacher, Technology Integrationist, Program Manager, and University Instructor. She has an M. Ed in Teaching and Learning. Connect with Angie on Twitter: @mrskalthoff and visit her website: bit.ly/angiekalthoff. Amanda Strawhacker is the Associate Director of the Early Childhood Technology (ECT) Graduate Certificate Program at Tufts University’s Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development. She holds a Master’s and Ph.D. in Child Study and Human Development, which she earned while designing and researching EdTech like ScratchJr and the KIBO Robot at the DevTech Research Group, and was a speaker with TEDxYouth@BeaconStreet. Connect with Amanda on Twitter: @ALStrawhacker and visit her website: amandastrawhacker.com

Amanda Strawhacker is the Associate Director of the Early Childhood Technology (ECT) Graduate Certificate Program at Tufts University’s Eliot-Pearson Department of Child Study and Human Development. She holds a Master’s and Ph.D. in Child Study and Human Development, which she earned while designing and researching EdTech like ScratchJr and the KIBO Robot at the DevTech Research Group, and was a speaker with TEDxYouth@BeaconStreet. Connect with Amanda on Twitter: @ALStrawhacker and visit her website: amandastrawhacker.com Dr. Amanda Sullivan is a researcher and educator whose work involves developing and evaluating new technologies and curricula for young children, with a specific focus on engaging girls in STEM. She is the author of the book Breaking the STEM Stereotype: Reaching Girls in Early Childhood. Contact Amanda on Twitter: @AASully, or visit her website: www.amandaalzenasullivan.com

Dr. Amanda Sullivan is a researcher and educator whose work involves developing and evaluating new technologies and curricula for young children, with a specific focus on engaging girls in STEM. She is the author of the book Breaking the STEM Stereotype: Reaching Girls in Early Childhood. Contact Amanda on Twitter: @AASully, or visit her website: www.amandaalzenasullivan.com